The Jump Line: Election Edition

Hello!

We’re going to do something a little different this time around since, as you might have heard, it is once again an election year. This means that you’ll be hearing about crime in seemingly every political ad, poll, and focus group (even when it isn’t a top voter concern). Over the next few months we’ll dedicate some space in The Jump Line to different angles and sourcing ideas for common electoral issues (you know – progressive prosecutors, immigration, bail reform, etc. – the usual suspects), and we’ll also spend some time talking about things we believe deserve more attention this election cycle. For example, we’ve been thinking a lot about disorder, and infrastructure, and what makes people feel safe.

But quickly, before we get into that…

We both live in Atlanta, which just went through a mini 6-day water crisis, which was not fun and also doesn’t compare to the much-longer-running water crises in multiple other American cities. But we’ll never miss an opportunity to highlight infrastructure collapse as the public safety issue that it is.

As usual, follow the fines and the lawsuits! Meris Lutz at the AJC looked into recent violations by the Atlanta Watershed – just weeks before the water main breaks, they were fined over $150,000 for sending illegally contaminated water into surrounding rivers.

And pay attention to what’s worrying the watchdogs. The Georgia Environmental Protection Division put out a report in March of this year detailing the watershed’s (multiple) other breaches that are polluting local waterways; the report describes a large Atlanta wastewater treatment facility as being filled with broken equipment, with growth and “solids” growing on the walls of the treatment basins. Not to state the very obvious, but perhaps nothing matters more for general community safety than access to clean water. (This resource bank has some helpful sourcing for water and other non-traditional public safety issues in Georgia and other states.)

Watch what happens

livenext. Atlanta has already been plagued by sinkholes, with a recent increase in incidence thanks to multiple main breaks (aging infrastructure) and floods (climate chaos). There’s sinkhole litigation to follow, and there could be lawsuits related to the water main break, too. We love to see outlets shifting resources to new beats/sections/verticals that cover overlooked safety issues. There are plenty of cool examples of this, even temporarily: for example, the Tampa Bay Times dedicated a section of coverage to a particularly intense bout of dangerous Red Tide algae in 2021. The Baltimore Banner has a beat surrounding the bridge collapse right now. We also just discovered the Wastewater Digest, which is an incredibly helpful resource for journalists covering water and other environmental issues. (You might be wondering – is there a sludge and biosolids subsection?! The answer is yes.)

OK. On to thinking about some election year stuff.

Perception vs Reality?

Crime and the criminal legal system are shaping up to be a central–and complicated–theme of this election cycle (the various goings-on in court for the families and candidates themselves aside!) The gulf between the reality and public perceptions of crime is growing wider1. According to the most recent national data, the murder rate dropped by 13% in 2023, the largest single year decline ever recorded, bringing the rate in line with where it was in 2016. Reported violent crime fell by nearly 6 %, bringing it to its lowest level since the 1960s. And reported property crime declined by roughly 4%, also leaving it near historic lows. If the metric you’re using is police-reported crime statistics, the country is rebounding from the increased violence (particularly the increase in gun homicides) of the early years of the pandemic.

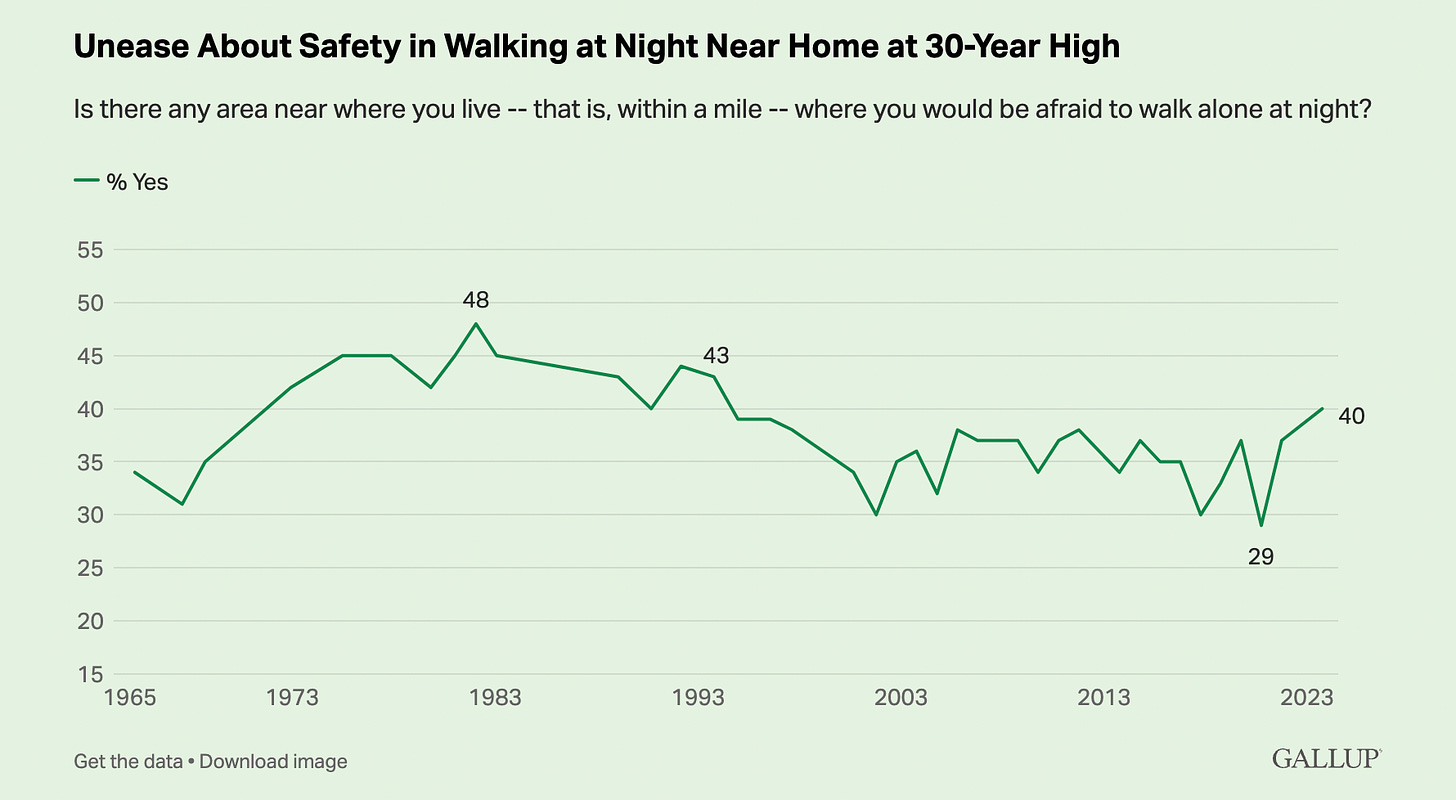

Despite all this, people aren’t feeling safe. In 2023, Gallup reported that the share of people afraid of walking alone at night reached a 30 year high, and the highest-ever percentage of people (more than 75%!) said they thought crime was increasing, even though reported violent and property crime declined to historic lows.

Now, it’s worth noting that Gallup asks these questions every year, and every year people think crime is increasing no matter what’s really going on. But the disconnect is wider than ever, and we think that merits attention especially in an election year. Here are a few explanations we’ve been considering, along with some good sources to talk to:

Lingering unease from the 2020-21 increase in gun violence: Gun violence –including homicide, suicide, and non-fatal shootings – increased significantly in 2020 and again, to a lesser degree, in 2021. Even though gun violence remained well below the highs of the 1980s and 1990s, that didn’t matter to the many people whose lives were upended by shootings. And even people who didn’t experience violence almost certainly heard about the increase in homicides, given the intense media focus. This has a measurable impact on people’s perceptions of their own safety.

The National Press Club did a great panel on best practices in covering gun violence, with The Guardian’s Abené Clayton, The Trace’s Jennifer Mascia, and The Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting’s Dr. Jessica Beard. It’s moderated by the Chicago Sun Times’ Kaitlin Washburn. You can watch it here.

Dr. Shani Buggs is a researcher at UC Davis and an expert on community-based violence reductions programs and access to guns. Some of her recent work looks at how kids are impacted by living near the site of gun violence, even if the exposure is indirect.

John Gramlich is an Associate Director at the Pew Research Center and the author of the above-linked analysis on recent gun violence.

Political anxiety: People’s perceptions of crime tracks closely with their political affiliation. According to survey data from Gallup, ever since 2001, Republicans have been more likely to believe crime is increasing when a Democrat is president, and Democrats have been more likely to believe crime is increasing when a Republican is president. This bias shows up in a bunch of ways – people are also more inclined to blame the sitting president for the price of gas if they didn’t vote for them; when it’s someone from their party they’re more likely to say it’s out of the president’s control. Researchers have several theories as to why this might be the case (what people hear from politicians they like, what they see/hear in the news they consume, what they notice around them). This political moment is unusual and highly charged, so it makes sense that the mechanisms driving this phenomenon might be operating on overdrive right now.

Zoe Towns, the Executive Director of FWD.us, and John Gramlich (also listed above for his analysis on gun violence) are experts in all-things-polling-related.

Visible poverty/suffering: It’s not surprising that people are feeling unsafe when you take into account how much suffering there seems to be, everywhere we look. Research shows that one of the biggest drivers of how safe people feel in their own neighborhoods is perceived sense of disorder – things like vacant buildings, vandalism, visible drug use, trash on the streets, etc. Seeing other people suffer also negatively impacts collective mental health and makes us feel unsafe. There’s a lot of struggle going on in the US right now: Rents are still increasing. They have been going up since the beginning of the pandemic, and more and more people are getting fully priced out of the housing market. On any given night, over 580,000 people in America are sleeping without homes, and it’s likely most of them feel pretty unsafe. Inflation is still very high, and 44 million people are food insecure. Deaths from overdoses – primarily from fentanyl – remain at historic highs, even after a small decrease in 2023. Some downtowns are bouncing back post-early-pandemic-years; some remain more empty than they were. Urbanist Jane Jacobs coined the term “eyes on the street” to describe the link between community safety and community vibrancy – communities with lots of people around make everyone feel safe, and that has changed with remote work. Basically: the early COVID years were traumatic and hard and while we’re generally moving in a positive direction there’s still a lot of visible suffering, and that impacts us.

Dr. Rakeen Mabud is the Chief Economist and Managing Director of Policy and Research at Groundwork Collaborative, which researches the correlation between crime and weakened social safety nets.

Dr. Jennifer Robinette is a professor and researcher focused on neighborhood disorder and perceived safety.

We’re interested in hearing about what you’re thinking when it comes to individual and community safety in the United States in 2024 – so much of this is hyperlocal. What are we missing? What else should we be thinking about? What seems to be driving perceptions of safety – or lack thereof – in the areas you cover? If you’re a public defender, what trends are you seeing in court? If you’re a teacher, what’s going on with your kids over the summer? Is infrastructure collapse impacting your city? We want to hear from you!

A quick note on what we mean when we say “crime.” Crime statistics in the United States focus on a small subset of crimes (murder, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft) that are tracked by police departments, most of which then send those numbers up to the FBI which publishes national statistics. For lots of reasons, that data paints a very incomplete picture of community safety. For one thing, those seven crimes probably aren’t the things that most determine whether or not someone feels safe, which almost certainly explains some of the disconnect between crime rates and perceptions of safety. If you want some tips on reporting on crime statistics, you can check out this explainer.