Welcome to The Jump Line!

Welcome to The Jump Line!

If you don’t know us, we’re Josie and Hannah.

Josie Duffy Rice is a writer and a (non-practicing) lawyer who focuses on prisons, prosecutors, and other criminal legal issues. She used to be president of The Appeal and is the host of Unreformed. Hannah Riley is a writer and communications expert who has worked with journalists in her roles at various criminal legal nonprofits over the years. Maybe you met her at one of the “law school for journalists” events she hosted at the Southern Center for Human Rights. Currently she’s the Director of Programming at the Center for Just Journalism. We both live in Atlanta but work nationally.

The work we do has made competing facts very clear to us: 1) people have endless stories to tell about the criminal legal system and public safety more broadly, 2) it’s not always easy for people to find those stories or get context on what’s happening in their community or around the world, and 3) it’s harder than ever for journalists to identify and investigate those stories. (More on that later.) The Jump Line is an attempt to bridge these gaps. Our goal here is to share things we’ve heard, seen, or read about that we think deserve more attention or can provide useful context to what’s out there already. It’s a place to talk about what we’re hearing and learn more about what’s happening. (If you were subscribed to our previous newsletters, we’ve included you on this list too!)

We decided to start this newsletter because we already spend pretty much all our time thinking about journalism and the criminal legal system. We consume a LOT of news – there’s no county too small or issue too obscure for us. (Other people have normal fun hobbies…this is ours.) Our DMs, inboxes, and voicemails are filled with stories that deserve more attention. They come from all over the place – defense attorneys, nurses, teachers, neighborhood group leaders, legislators, and friends and family of people in the system. Some of the things we hear are horrifying, some hopeful. Most of it we think the public should know about.

So yes, if you’re a journalist, this is a newsletter for you. But if you aren’t a journalist, we think it’ll be a great resource for you, too. If you care about the criminal legal system - if you care about public safety at all! - we think you’ll enjoy it. And it’s free!

We also hope that y’all will share stories and ideas with us – if you have a newsworthy story/trend/person in mind, or have read something you think we should know about, please let us know.

We’ll get to stories in just a minute, but since it’s our first issue, we wanted to say a little more on those “competing facts” we mentioned above. First, the scope of our criminal legal system is still tremendous. Just a few stats for you:

The United States has 18,000 police departments, 2,300 prosecutor offices, and 6,300 jails, prisons, and other detention facilities.

Every year, there are about 1.3 million people in prison and a shocking 10 million admissions to local jails. (TEN MILLION.)

At last count, there were more than 18 million criminal cases a year.

One in two American adults has had an immediate family member in jail or prison.

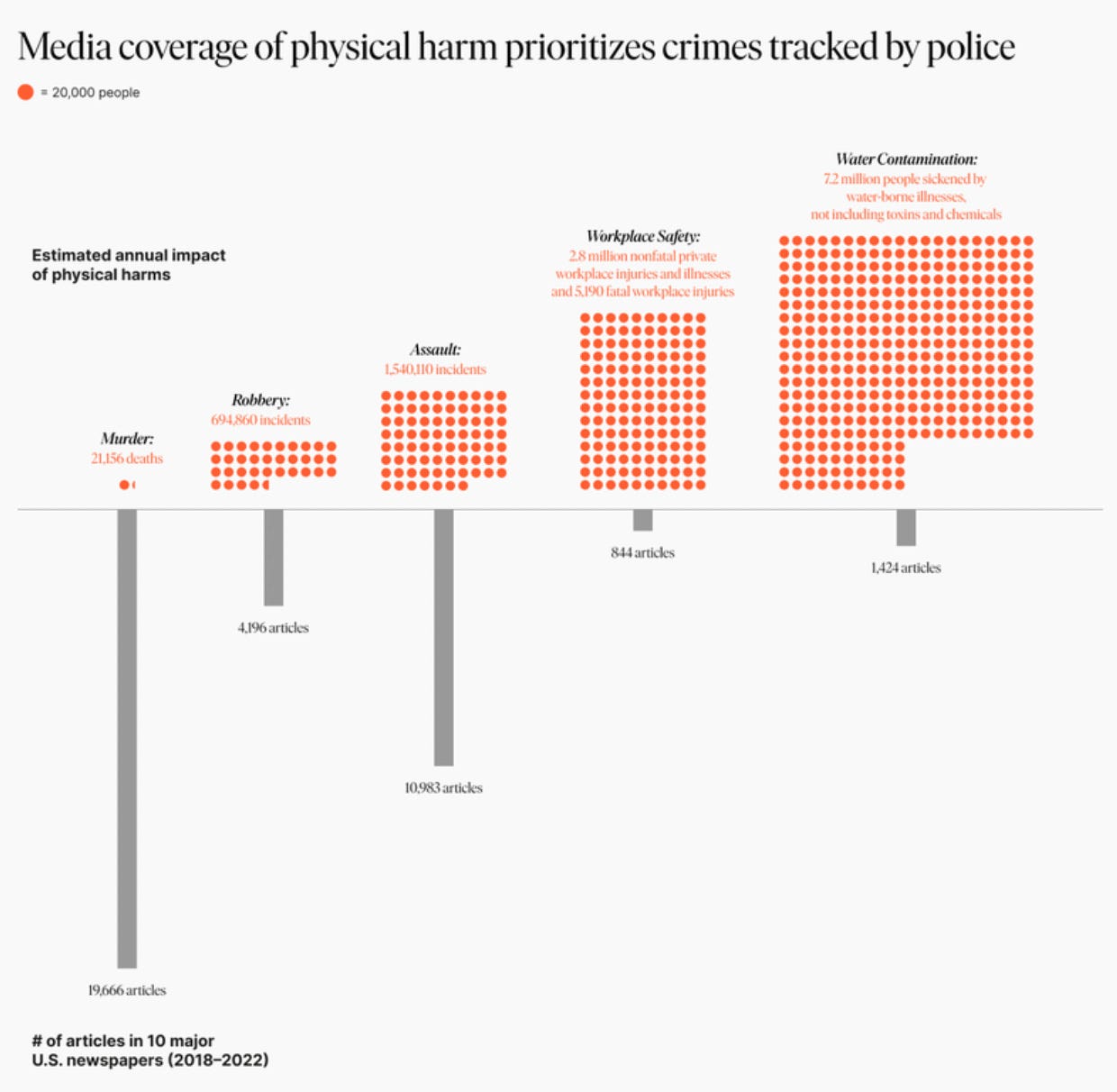

One of the many harms of this leviathan is that it sucks up a lot of media attention, meaning a lot of stories about public safety and community wellness that don’t involve the criminal legal system never get told. We think of safety as something that involves police or prisons, because that’s where a lot of the media focus is. Other stories about public safety don’t get framed that way – like, for example, coverage of housing code violations, workplace injuries, and chemical pollution. As you can see below, the news media tends to prioritize coverage of a narrow subset of crimes, while ignoring other harms. But those other harms are also public safety issues.

As all these stories continue to pile up, there are fewer journalists with fewer resources to tell them. Northwestern University’s State of Local News project paints a bleak picture. Since 2005, the country has lost nearly one-third of its newspapers and almost two-thirds of its newspaper journalists. About half of the country’s 3,143 counties have only one news outlet. More than 200 counties have no local outlets at all. The journalists that remain no longer inherit a rolodex of trusted sources; they don’t even have a usable version of Twitter anymore.

We know we can’t replace a rolodex or Twitter (RIP), but we can offer some of the tips we receive directly — along with whatever resources we can provide — to the people who remain committed to telling stories about community safety in spite of the incredibly challenging media landscape around them. So, let’s get into it!

What’s your local police foundation up to?

Police foundations are local non-profit organizations that provide additional funding to local police departments. But as you can imagine, they aren’t your typical non-profits — often, the donors are members of the boards and C-Suites of powerful companies in the area. The money given by police foundations can be used in different ways — for general police operations or to fund specific projects, like new surveillance technology, training facilities, or military-style equipment.

Why we’re thinking about it:

We’ve read lots of great local and national reporting on police foundations that can provide a guide for journalists interested in covering this issue in their own communities:

The Chronicle of Philanthropy published an in-depth piece by Jim Rendon on police foundations, with a particular focus on the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF.) APF has been in the spotlight for its role in funding the controversial, $90+ million police training center known as Cop City. The Atlanta Community Press Collective followed this up with an investigation into the Atlanta Police Foundation’s relationship with Taltrix, an electronic surveillance and monitoring company now attempting to use video surveillance on people released pretrial in the city. And Tim Pratt at The Guardian is tracking a lawsuit making its way through Georgia courts alleging that the Atlanta Police Foundation ignores requests for public records.

Kevin Rector and Libor Jany at the LA Times investigated the role of the Los Angeles police foundation; in St. Louis Jeremy Kohler did the same.

Angles to consider:

Who funds and operates your local police foundation?

Color of Change researched 23 police foundations across the country, including their budgets, donors, and projects.

What projects does your local police foundation fund?

Check out your local police foundation’s website. You might find something interesting. For example, the Houston Police Foundation has some crowd-fundable items on their website, like chipping in for an armored crew cab truck, sponsoring a police horse (you get to choose the name, which will go on the saddle!), or buying a personalized brick at the new training facility. In Chicago, you can buy a police dog a new bulletproof vest. The Los Angeles Police Foundation has a page where you can donate crypto. In St. Louis, the police foundation funds Operation Polar Cops, an ice cream truck run by police officers.

The same Color of Change report has information on the projects funded by 23 large police foundations.

Are there opportunities for public input on your local police foundation’s activities? And are they transparent about their activities?

A few years ago, Michael Leo Owens, Tom Clark and Adam Glynn reported for the Washington Post on where police officers get their militarized protective gear and found that the police foundation funds are often the hardest to trace.

But on a hopeful note, transparency-wise: in New York City, the City Council introduced legislation that would require the NYPD to disclose how it spends the private money it receives from the New York City Police Foundation.

Infrastructure week?

We want to make sure that we’re including public safety stories outside of the narrow lens of the criminal legal system. The collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore raises many questions about public safety that might be relevant in your community: infrastructure design, working conditions, and safety protocols at large transit corporations.

Why we’re thinking about it:

Journalists have played a really important role in helping people understand the specifics of the terrifying and tragic incident and its broader context and implications. A team at The Baltimore Banner – Ben Conarck, Hallie Miller, and Daniel Zawodny – has been asking good questions about the design of the bridge. At the New York Times, Michael Forsythe, Peter Eavis and Jenny Gross reported on the history of labor violations at the shipping company that owned the vessel that hit the bridge, including forcing employees to remain on the ships for months past their contract’s expiration, wage theft, and more. Meanwhile, David Sirota, Helen Santoro, Freddy Brewster, Lucy Dean Stockton, and Katya Schwenk at The Lever brought attention to the fact that Maersk, the company that chartered the ship, had recently been sanctioned for preventing its employees from reporting safety violations directly to government regulators, in violation of whistleblower protection laws. (This particular element of the story echoes accusations made against Boeing for its treatment of whistleblower John Barnett.)

Angles to consider:

Are the bridges in your community safe?

You can peruse a list of the most-traveled structurally unsound bridges in the United States, thanks to the American Road and Transportation Builders Association. Heads up to West Coast journalists–there are a lot of bad bridges in California.

Are people in your community also experiencing unsafe working conditions?

You can find resources for investigating on-the-job injuries, wage theft and other workplace safety issues in OSHA's severe injury reports, the Department of Labor's enforcement data, a violation tracker compiled by Good Jobs First, and our very own resource bank.

The conditions faced by immigrant workers are often especially dangerous, not just in Baltimore but in communities across the country. Here’s a list of industries that disproportionately employ immigrants, which could be a jumping off point for an investigation of working conditions in your own community.

What else are whistleblowers trying to warn us about?

The whistleblower settlement against Maersk received scant media attention before the bridge collapse. Tracking and reporting on whistleblower complaints could help prevent future tragedies.

There are important privacy considerations when it comes to whistleblowers, but the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration regularly puts out press release updates on whistleblower cases, and OSHA also has good data on workplace safety, if you want to cross-reference whistleblower complaints and safety violations. The Securities and Exchange Commission also puts out press releases in their whistleblower cases. All of these should provide good leads.

Other stuff:

Local reporters Colleen Heild and Matthew Reisen uncovered a scandal unfolding in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Several Albuquerque police officers are accused of working with a local defense attorney to dismiss DWI cases in exchange for money. The details are wild. You can read one person’s account of being framed for drunk driving and extorted for $8,500 here. In keeping with what appears to be this week’s theme, the story also involves a whistleblower who wrote to the local Civilian Police Oversight Agency.

Speaking of misconduct, we’re also following the story of a now-disbanded homicide unit in St. Joseph County, Indiana that allegedly placed people accused of murder in cells next to or with informants to whom the state had fed information. With the help of prosecutors, the informants would also allegedly fabricate testimony in order to secure a conviction. The local journalist that broke the story (ABC57’s Tim Spears) had a hand in this man’s release after it came to light that he may have been convicted based on fabricated testimony. More cases are likely to be impacted.

The stories out of New Mexico and Indiana are united by a common thread: anomalous data points. The attorney accused of misconduct in the Albuquerque scandal had a DWI dismissal rate of about 90% when working with the officers in question, compared to the average of 26-30%. When the St. Joseph County Metro Homicide Unit was handling all of the murder investigations for three different police departments, they also had a higher-than-average clearance rate – their 80% versus the national average of 62% over the same time period. The lesson here is if you see something that looks unusual, dig a little deeper. That data might just be too good to be true.

A few more small things:

Worth reading out of Philly: Nate File of the Philadelphia Inquirer reports on this $818K initiative which aims to prevent gun violence with street cleaning.

Worth reading out of Baltimore: For WYPR, Rachel Baye, Jennifer Lu and Claire Keenan-Kurgan report on kids in the adult criminal system – a Baltimore City judge, for example, said a teenager’s large size was an argument to keep him in the adult system.

On Friday, April 12, Center for Just Journalism is hosting a free Zoom webinar for journalists on best practices for covering RICO prosecutions. Hear from Atlanta reporters and attorneys who have been steeped in both the YSL and the Cop City RICO cases. Register for the 12 - 1:30 EST webinar here.

And just a couple other newsletters we love - The Appeal, The Marshall Project, and Local Matters.

So that’s it for Newsletter #1! Remember, this newsletter is free, and will remain free. Share with your colleagues, friends, and anyone else you think might be interested! Please let us know what we can do to make these newsletters as useful as possible to you. And if you have a story idea, tell us about it! You can comment on this post or respond to this email. (We’re working on setting up an encrypted tool, too, so you can send anonymously!) We’d love to hear from you.