Heat Islands, the Right to Hug, Bail Funds, and More

Hello and Happy July!

This month, we’re thinking about jails and their shifting populations and policies – who is held and why, who is allowed to pay for their release, who is allowed to visit and how. It’s top of mind because we got a tip from someone about an especially dysfunctional weekend at Atlanta’s DeKalb County Jail in June (more on that later). We’ve also been thinking about deadly heat (a sort of inescapable part of the American experience the last few weeks).

Jails, Jails, Jails

Why are we thinking about this?

Someone wrote to tell us that over the course of a weekend in June, people incarcerated at the DeKalb County Jail received signature bonds (a form of pretrial release that doesn’t require money, just the promise to return to court) on Saturday morning, but didn’t actually leave the jail until around 11 PM Monday night (despite the automated system recording them as having been released). Other people were told, after inquiring about the status of their bonds, that the “system was down” – for 2+ days. We’ve heard similar tips about the Fulton County Jail (also in metro Atlanta) holding people far past when the system says they’ve been released. Two things: if you’re a journalist in Atlanta who is interested in covering this story, send us an email and we can connect you with this source. Secondly, is this also happening in jails where you live? Let us know!

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp recently signed Senate Bill 63, which added dozens of new offenses to the list of charges that require cash bail and eliminates charitable bail funds. The bill was supposed to go into effect on July 1, but parts of it were temporarily blocked by a federal judge after a lawsuit brought by the ACLU of Georgia. If litigation goes the government’s way, a charitable bail fund in Georgia will only be able to bail out three people – yes, three – per year. Bail bondsmen will continue to function as usual (albeit with more business).

We’ve also had jails – and jail visitation – on the brain because of this recent litigation brought by Civil Right Corps in Michigan, which challenges the constitutionality of recent bans on in-person visitation.

Opportunities for Reporting

What’s happening with bail funds nationally?

Georgia’s SB 63 is in the news right now, but other states have been chipping away at collective aid through bail funds. The American Bail Coalition wrote model policy to counteract what they perceive as the growing strength – and disruption to the profitability of the bail industry – of bail funds nationally. Legislation is already starting to crop up in other states: The Safer Kentucky Act would bar charitable bail funds from paying bails set at $5,000 or more. Virginia and Washington proposed new licensing and reporting requirements for bail funds, and Tennessee attempted to bar court clerks from accepting cash bail from charitable bail funds. Last year, the Seventh Circuit upheld an Indiana law that prohibited bail funds from freeing people charged with violent offenses or convicted of violent offenses in the past, among other restrictions.

Reporting on bail tends to focus on the times that something goes wrong, which obscures the much more common phenomenon of people awaiting trial at home — with their kids, working their jobs, sleeping in their own beds — without incident. Coverage of charitable bail funds, which are responsible for thousands of successful releases every year, offer an opportunity to tell these overlooked stories.

Sorry for the semi-shameless organizational plug, but the Center for Just Journalism has an issue brief on bail, which summarizes the research and compares results from various jurisdictions’ attempts at bail reform.

Right to Hug

New “right to hug” litigation brought by Civil Rights Corps challenged the legality of jail visitation policies in two Michigan counties, both of which fully eradicated in-person jail visits and replaced them with costly video calls. A lot of jails have banned in-person visits, even before the pandemic, and there are ample opportunities for local and national reporting on these policies and their impacts. Check out if your local jail still has in-person visitation, and if not, there are lots of jump-off points for reporting from there:

Find the contract that defines the relationship between your county jail and its telecom provider – start here to see if the Prison Policy Initiative has already found the contract for your county. (Is that contract missing? You can submit an information request. Here is an example.)

Look at the county budget. The Sheriff’s department may have a line item for phone, video, tablet, and messaging revenue. If you can’t easily find the telecom contract, submit an information request for the revenue. Here’s an example.

More shameless organizational promotion for the greater good – this issue brief from Center for Just Journalism has more ideas for how to investigate telecom contracts and the general chipping away of in-person visits, as well as further resources for reporting (like this Prison Policy Initiative research roundup on the positive impacts of in-person visits.)

Hot Hot Heat

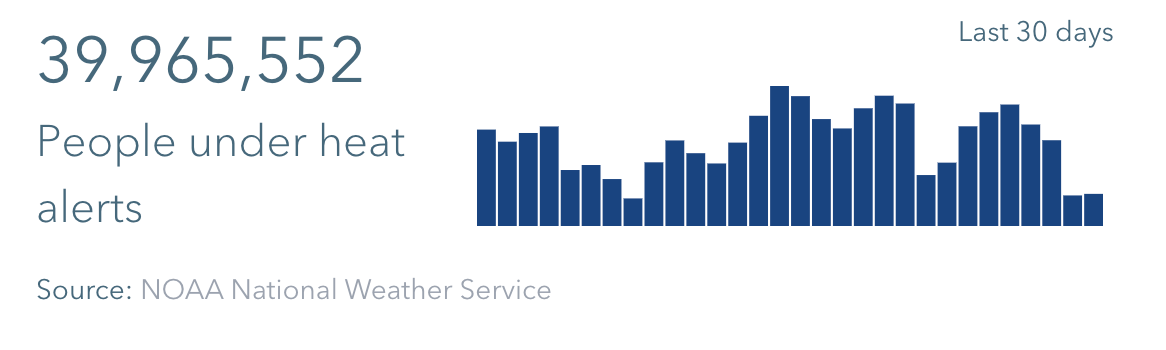

This will be news to absolutely no one, but: it’s hot! June was the hottest June on record and the 13th consecutive hottest month on record, with 14.5% of the world’s surface reporting record heat, beating June 2023 by 7.4%. It’s probably totally fine.

Why We’re Thinking About It

Heat is deadly. It’s deadly on its own – from incarcerated people boiling to death in concrete cages (read this recent, horrifying piece by Sam Levin at The Guardian about a heat death at a California prison) to elderly folks dying at home without air conditioning (like this 78 year old who died of hyperthermia in Houston after having no power for days). Heat also brings along with it other risks, like destructive pop-up storms and the possibility of increased interpersonal violence.

Opportunities for Reporting

If you’re an investigative journalist or anyone who has a little flexibility with time on your assignments, consider doing a deep dive into the heat-related experiences of a community over a summer (or even just over a particular week or particularly intense heat-wave). There’s remarkable temperature variability in neighborhoods that are actually quite close to each other. This is because redlining and other racist policies prioritized things like tree canopy, more greenspace, better drainage, etc. in white neighborhoods, and neglected to do any kind of mitigation in historically Black neighborhoods. This can result, for example, in a temperature difference of 10 degrees over just 2 miles.

Check and see if there has been a heat map done of your city/community. That can be a starting point for finding a neighborhood to cover.

The EPA maintains a Heat Island Community Actions database, which catalogs cooling projects already in action in communities across the US. The projects are varied, and some are quite creative.

There are also things like Depave — a project operating in Chicago, Portland, and other communities in the US and Canada — which works to reduce urban heat by “greening” concrete spaces. The less asphalt and concrete there is in a city, the less risk it has of experiencing heat island effects as well as serious flooding. Lucy Sheriff covered the Depave movement in The Nation last year, but there are ample opportunities for local follow-up reporting.

The federal government’s National Integrated Heat Health Information System tracks heat equity across the country. Deadly heat and extreme flooding are worse in poor non-white communities. The dearth of green space in those neighborhoods, while wealthy white neighborhoods often have plenty, is a direct result of redlining. This 2024 study from Nature Cities found that even decades after the discriminatory redlining policies were outlawed, the negative climate impacts remained. The still-heightened vulnerabilities were, the authors found, a result of “diminished environmental capital” in those neighborhoods—notably reduced tree canopy and lower construction foundation height.

Almost a century ago, the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and tasked it with creating “Residential Security” maps of American cities. HOLC’s maps documented how loan officers and appraisers evaluated mortgage lending risk in the years leading up to the 1950’s. Neighborhoods deemed “hazardous” would get redlined by mortgage lenders, ensuring they got no access to the kinds of investment needed to improve the housing and economic opportunity of the residents. You can find those archived maps here and compare them to current day heat islands.

There are a number of useful pieces of research into the impacts of heat in specific places. For example: In Portland, Oregon, the City’s Bureau of Emergency Management spent a summer tracking temperatures and the heat-related experience of the residents in several public housing properties. In the greater Boston area, volunteers heat-mapped the Mystic River Watershed area by neighborhood.

Just a Few More Things We’re Thinking About/Reading

The FCC unanimously voted to reduce the price of video and phone calls for incarcerated people! The new rules more than halve the per-minute rate caps for all prison and jail phone calls, set up per-minute rate caps for video calls, and prohibit all fees. It’s a pretty big thing! We’re going to get into it more in the next issue.

The right to hug litigation resulted in this beautiful New Yorker piece by Sarah Stillman. (Of course, journalists have been sounding the alarm on reduced in-person visitation for years – this excellent Quartz piece by Hanna Kozwoltza is from 2015, which is somehow almost a decade ago.)

As you know, we do love a co-reporting project and this New York Times x Baltimore Banner piece is no exception. Alissa Zhu, Nick Thieme, and Jessica Gallagher report on Baltimore’s response to the surge in opioid overdose deaths in older people, particularly Black men aged 50-70.